DiagnosticInnovationPrevention A 15-minute scan could help diagnose brain damage in newborns

A 15-minute scan could help diagnose brain damage in babies up to two years earlier than current methods. The study, supported by the NIHR Imperial BRC and the MRC, involved scanning over 200 babies at 7 hospitals across the UK and USA. Using a type of brain scan called magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy, the researchers predicted brain damage with 98% accuracy.

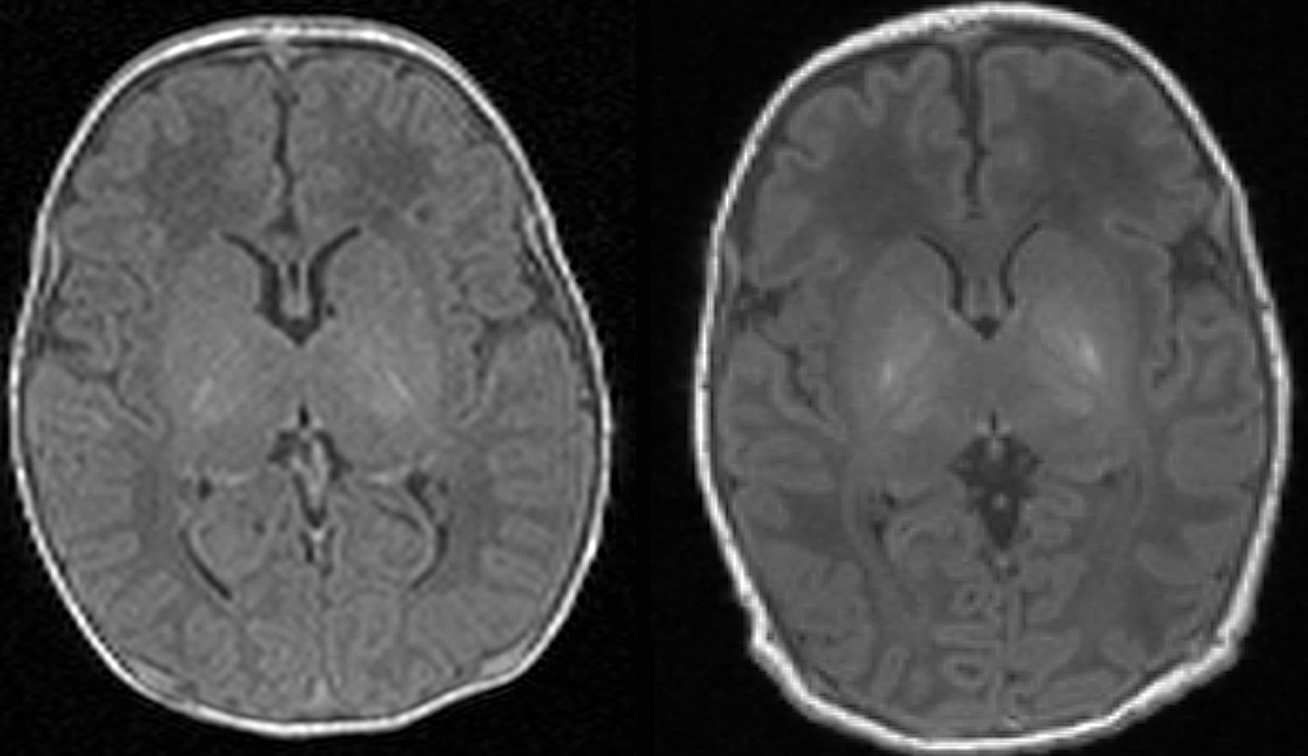

Brain damage affects around one in 300 births in the UK, and is usually caused by oxygen deprivation. However, currently doctors are unable to accurately assess the extent of a newborn baby’s brain damage. Any child suspected of having some type of damage is given an MRI scan shortly after birth. This allows doctors to look at black and white pictures of the brain to see if any areas of the brain look lighter than others, as this may suggest damage. Doctors then use this information to give parents an estimation of the extent of the damage, and the possible long-term disabilities their child may face.

However, this method is only between 60-85% accurate, and relies heavily on the radiologist’s individual judgement, meaning the prognosis can vary depending on who assesses the scan, and where the scan is done. Hence the health professionals can only confirm if a child has lasting brain damage when they reach two years old, by assessing whether a youngster has reached their development goals such as walking and talking. In the new study, scientists used MR spectroscopy to assess the health of brain cells in an area called the thalamus, which coordinates a number of functions including movement, and is usually most damaged by oxygen deprivation. The scan specifically tests for a compound called N-acetylaspartate – high levels of which are found in healthy brain cells, called neurons. A level of 9-10 is found in healthy neurons, whereas a level of 3-4 indicates damage.

The technology used is the same as that needed for an MRI scan, and only requires the baby to spend an additional 15 minutes in the scanner. In the new trial, published in the journal Lancet Neurology, the scan was performed at the same time as the routine MRI scan when a baby was between four and 14 days old. The scan does not carry any additional cost to the NHS, and the data can be easily analysed using special software by any radiographer.

Dr Sudhin Thayyil, Director of the Centre for Perinatal Neuroscience in Imperial’s Department of Medicine said: “At the moment parents have an incredibly anxious two-year wait before they can be reliably informed if their child has any long-lasting brain damage. But our trial – the largest of its kind – suggests this additional test, which will require just 15 minutes extra in an MRI scan, could give parents an answer when their child is just a couple of weeks old. This will help them plan for the future, and get the care and resources in place to support their child’s long-term development.”

In the trial, all of the babies had received so-called cooling therapy immediately after birth. This is now a routine treatment for newborns with suspected brain damage and involves placing a baby on a special mat that reduces their body temperature by four degrees. Evidence has shown that cooling the body can help reduce the extent of brain damage and reduce the risk of long-term disabilities. The babies then had their brain scan soon after this therapy, and detailed developmental assessment at two years of age. The results suggested the MR spectroscopy at 2 weeks accurately predicted the level of toddler’s development at two years old.

Dr Thayyil added that the scan may also help scientists develop new treatments to tackle brain injury in babies: “At the moment, when doctors are trialling a new therapy that may boost development of children with brain damage, they must wait two years until they can assess whether the treatment is working, and need to study a large number of babies. But with this new scan, they’ll be able to assess this almost immediately, with a much smaller number of babies.”

He added that the next step is to roll out the scan in more hospitals in the UK as a clinical tool. “Most NHS hospitals already have the facilities and software to perform this scan, it’s just a case of increasing awareness and training.”

Case study

Christine Reklaitis gave birth to her daughter Georgiana in 2015, and took part in the trial at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in London. She said: “I had a healthy pregnancy, but during labour my midwife struggled to find Georgiana’s heartbeat, and she was born shortly afterwards via emergency c-section. I remember the terror when we didn’t hear a cry after she was born, and the team immediately started to resuscitate her. Thankfully she was soon breathing and was whisked away to intensive care, and placed in an incubator. The doctors told us they were going to cool her down, which we thought sounded unusual, but were told it would reduce her risk of brain damage.

We were asked to take part in a trial and quickly agreed. We felt our daughter’s treatment benefitted from past studies, so we wanted to help develop future treatments. After the first MRI scan done at the Queen Charlottes and Chelsea Hospital on the day she was born, we were told the levels of a compound in her brain cells were low but were incredibly relieved when a scan a week later showed the levels had increased to normal levels. She has since hit all her development goals and is a normal three-year-old and full of energy. We joke the cooling treatment has stayed with her, as she never wants to wear a coat when we go outside. We are so pleased we took part in this trial – and we’ll be very proud if this helps other families.”

Read the full story by Kate Wighton, Imperial College London here.