TherapeuticTraining Research-informed nutritional care for cancer patients

Research into nutritional care for patients undergoing haematopoietic cell transplantation resulted in a change of routine clinical practice.

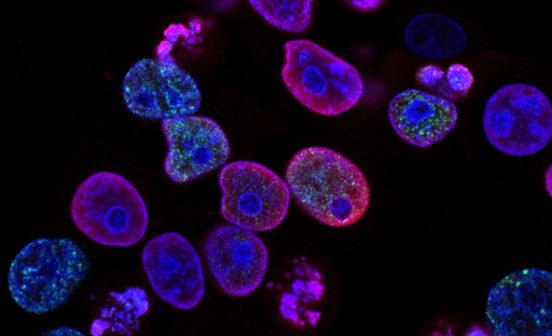

Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation is used for treatment of haematologic malignancies, where a patient receives blood-forming stem cells from a donor. In preparation for a transplant, patients receive intensive conditioning, which may include high-dose chemotherapy, with or without total body irradiation, causing significant inflammation of the membranes lining the gastro-intestinal tract. This in turn affects food intake for the patient, particularly oral intake, with many individuals consuming less than 60% of their energy requirement.

With little data available to inform nutritional recommendations for these patients, Ms Julie Beckerson, a specialist haemato-oncology dietitian at Hammersmith Hospital, set out to address this challenge, with financial support from Imperial Health Charity and NIHR Imperial BRC. Findings from her research fellowship were recently published in journal Clinical Nutrition, and she wrote the following entry for the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust blog:

“Nutrition practices in patients undergoing stem cell treatments can vary widely from one hospital to the next – partly because of the lack of research in this area.

Through my research, I wanted to understand exactly what this group of patients are eating and drinking, and how their body composition is affected. We know many struggle to eat normal food, relying instead on feeding tubes or intravenous nutrition, and I wanted to gain an understanding of which of these methods is more effective. I also wanted to determine a set of measurements to help clinicians establish a fuller picture of each patient’s nutritional health.

My manager encouraged me to apply for Imperial Health Charity’s research fellowship so I could have some funded time to collect and analyse data, with the aim of improving the nutritional care we provide to patients. The fellowship paid the salary of a band six dietitian to do my day-to-day clinical duties, freeing up most of my time to run the study and gather data.

More effective measurements

Normally when we assess a patient from a dietary point of view, we measure their weight and body mass index (BMI). But patients undergoing stem cell treatment receive a lot of intravenous (IV) fluid, which can affect the measurements. We might have someone that doesn’t eat for a week, but their weight isn’t going down because the IV fluid builds up in their body.

During the course of my research, we began carrying out much more detailed measurements, looking at the mass, strength and function of muscles to understand how well-nourished patients were. It threw up some really interesting results and we were one of the first studies to identify sarcopenia – muscle weakness and wasting – in haematology patients.

Our tests showed that even though only three of the 50 patients in the study had a low BMI, 60 per cent had sarcopenia. By looking at these patients, you would have thought they were all a healthy weight and size, but the more detailed tests showed there was something wrong and we wouldn’t have usually detected it.

Improved patient engagement

Something I didn’t expect was how engaged patients would be and how they would want to take and understand the measurements.

I found spending that extra 10-15 minutes with each patient taking the measurements, assessing their muscle tone, strength and function, made a really big difference to them. Those additional measurements helped them to focus on how important it is to keep eating well while in hospital and how they can engage with the nutritional aspect of their treatment.

Changes on the ward

As a result of my research, we are now incorporating these more advanced body composition measurements into our routine practice for patients undergoing stem cell transplants.

My research also highlighted how the longer patients stayed in hospital, the worse their protein intake became. It allowed me to secure a high-protein supplement drink that we now give to patients on the ward. As a result of my fellowship, and the retrospective data analysis I conducted, we now have evidence that gastric-tube feeding is preferable to intravenous nutrition for this group of patients.

Thanks to the Charity’s support, myself and my colleagues are able to recommend more confidently the right route of nutritional support for patients. And if we can improve each patient’s nutrition, we can improve their chances of a positive outcome following their stem cell transplant.”

Applications for the next round of research fellowships, funded jointly by Imperial Health Charity and NIHR Imperial BRC, close at midday on 31 January 2019. To find out more about the programme, visit Imperial Health Charity’s website.