InnovationPrevention Bacteria-fighting cells in the airways increase infection risk from respiratory viruses

Bacteria-fighting immune cells in the nose and throat may explain why some people are more likely to be infected by respiratory viruses.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common respiratory virus which typically causes the symptoms of a common cold in healthy adults. However, in infants and the elderly it can lead to thousands of hospitalisations each year and can be fatal.

Once infected, the virus enters the respiratory system through the windpipe (trachea) and makes its way down to the smallest airways in the lungs (the bronchioles). The infection causes the bronchioles to become swollen (inflamed) and increases the production of mucus. The mucus and swollen bronchioles can block the airways and make breathing difficult.

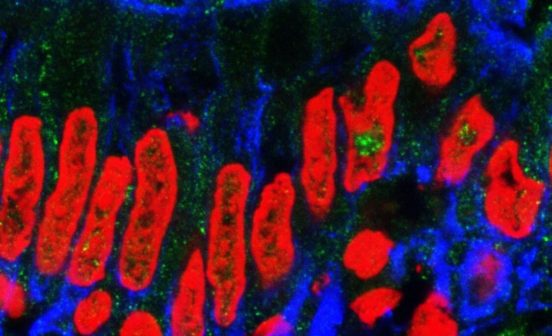

In a new study supported by the NIHR Imperial BRC, researchers have found evidence that individuals who succumbed to infection from RSV had more specialised white blood cells called ‘neutrophils’ in their airways before exposure to the virus, compared to those who staved off infection. These immune cells are known to release proteins which help create an antibacterial environment in response to a threat. The researchers believe this antibacterial immune response makes a host more susceptible to RSV by effectively switching off the early warning system and letting viruses slip through the net to cause infection.

Dr Ryan Thwaites, from the NIHR Imperial BRC Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Theme and co-first author for the study, said: “If we think of a group of 10 people all exposed to the same strain of RSV under identical conditions, we’d expect around six of them to become infected and show symptoms, but the rest may be unaffected. To date, we have been unable to fully explain exactly why this is and why, under the same conditions, some people are more likely to succumb to respiratory viral infections. But this study offers tantalising insights into how we might improve defences against respiratory viruses, and potentially even COVID-19.”

These findings could help researchers understand why people respond differently to the same viral threat, predict who is more at risk of infection, and even lead to preventative treatments to protect against RSV and potentially other respiratory viruses, including influenza and coronaviruses.

Read the full story by Ryan O’Hare here. © Imperial College London