First in HumanInnovation Potent psychedelic DMT mimics near-death experience in the brain

A new study by researchers at Imperial College London has shown that a powerful psychedelic compound found in ayahuasca can model near-death experiences in the brain. Near-death experiences, or NDEs, are significant psychological events that occur close to actual or perceived impending death. Commonly reported aspects of NDEs include out of body experiences, feelings of transitioning to another world and of inner peace, many of which are also reported by users taking the substance N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT).

DMT is a potent psychedelic found in certain plants and animals, and is the major psychoactive compound in ayahuasca, the psychedelic brew prepared from vines and leaves and used in ceremonies in south and central America. The researchers set out to look at the similarities between the DMT experience and reports of NDEs. Their findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, reveal a large overlap between those who have had NDEs and healthy volunteers administered DMT.

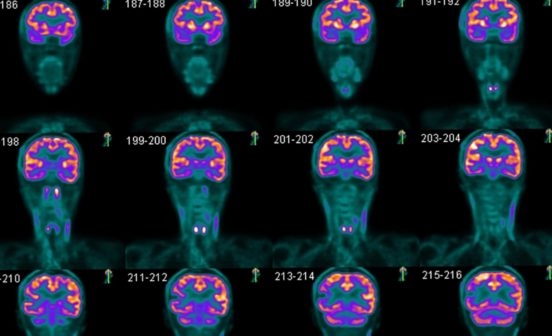

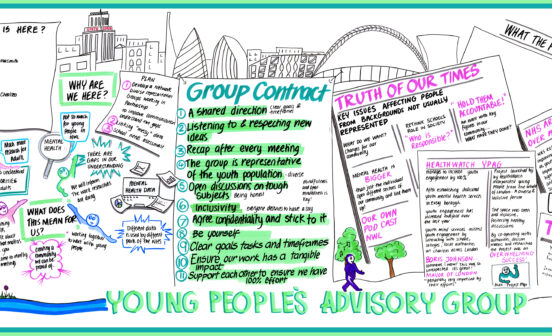

As part of the trial, the team looked at 13 healthy volunteers over two sessions, who were given intravenous DMT and placebo, receiving one of four doses of the compound. The research was carried out at the NIHR Imperial Clinical Research Facility and supported by the NIHR Imperial BRC. All volunteers were screened and overseen by medical staff throughout. Researchers compared the participants’ experiences against a sample of people who had previously reported actual NDEs and who had completed a standardised questionnaire to try and quantify their experiences. The group were asked a total of 16 questions including ‘Did scenes from your past come back to you?’ and ‘Did you see, or feel surrounded by, a brilliant light?’

Following each dosing session, the 13 healthy volunteers filled out exactly the same questionnaire to find out what sort of experiences they had whilst on DMT and how this compared to the NDE group. The team found that all volunteers scored above a given threshold for determining an NDE, showing that DMT could indeed mimic actual near death experiences and to a comparable intensity as those who have actually had an NDE.

Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, who leads the Psychedelic Research Group at Imperial and supervised the study, said: “These findings are important as they remind us that NDEs occur because of significant changes in the way the brain is working, not because of something beyond the brain. DMT is a remarkable tool that can enable us to study and thus better understand the psychology and biology of dying.”

Professor David Nutt, Edmond J Safra Chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial, said: “These data suggest that the well-recognised life-changing effects of both DMT and NDE might have the same neuroscientific basis.”

PhD candidate Chris Timmermann, a member of the Psychedelic Research Group at Imperial and first author of the study, said: “Our findings show a striking similarity between the types of experiences people are having when they take DMT and people who have reported a near-death experience.”

The researchers note some subtle, but important differences between DMT and NDE responses, however. DMT was more likely to be associated with feelings of ‘entering an unearthly realm’, whereas actual NDEs brought stronger feelings of ‘coming to a point of no return’. The team explain that this may be down to context, with volunteers being screened, undergoing psychological preparation beforehand and being monitored through in a ‘safe’ environment.

“Emotions and context are particularly important in near-death experiences and with psychedelic substances,” explains Timmermann. “While there may be some overlap between NDE and DMT-induced experiences, the contexts in which they occur are very different. DMT is a potent psychedelic and it may be that it is able to alter brain activity in a similar fashion as when NDEs occur. We hope to conduct further studies to measure the changes in brain activity that occur when people have taken the compound. This, together with other work, will help us to explore not only the effects on the brain, but whether they might possibly be of medicinal benefit in future.”

The authors caution that while the initial findings are interesting, they advise against self-medication with ayahuasca.

Article provided by Ryan O’Hare, Imperial College London