Diagnostic Brain imaging tool falls short for human tissue

A common research tool used to measure brain inflammation and test new dementia drugs may not be as helpful as scientists had hoped.

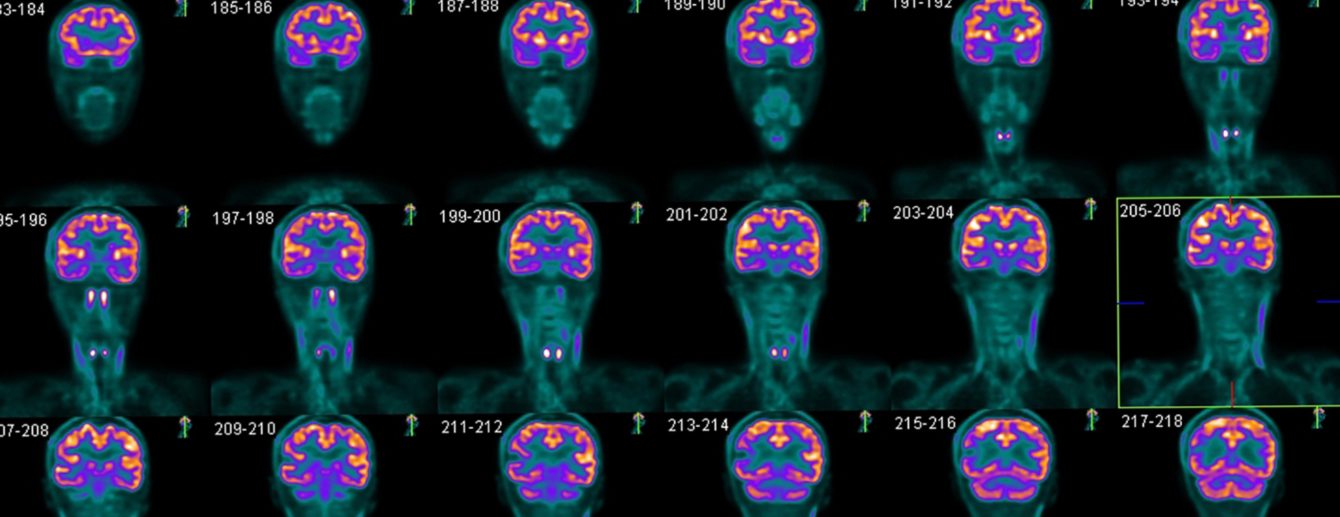

In clinical research, scientists use a type of imaging called positron emission tomography (PET) to gain a detailed view of what’s happening in the brain.

One of the markers targeted by scans, called translocator protein (TSPO), has long been used to measure inflammation driven by microglia – the specialised immune cells in the brain which respond to damage and disease.

This doesn’t mean the technique isn’t valuable as a research tool, but in many situations it’s not as helpful as we’d previously thought Dr David Owen Department of Brain Sciences

Microglia are known to be very active in many brain diseases, including Alzheimer’s Disease, and TSPO was believed to be a reliable signal of active microglia which can be easily shown with PET scans.

For example, in drug development reduced TSPO may be an indicator that a new drug is working as hoped, meaning the brain’s immune cells are less active.

But a recent study led by researchers at Imperial College London has found while this may be true in rodents like mice and rats, it is not the case in humans, where the signal may be far less reliable.

In a paper, published recently in the journal Nature Communications, they found that while TSPO does indeed increase when microglia become active in rodents, this does not happen in humans. The researchers analysed animal and human brain tissue to search for elevated TSPO and analyse the structure of tissue.

In brain tissue of people with Alzheimer’s Disease, Motor Neuron disease and multiple sclerosis (where microglia are activated), they found TSPO was not a marker of activated microglia as in rodent brains.

Analysis also showed TSPO is produced by multiple cell types in the brain, meaning the signal is far less clear. In human tissue, TSPO was also associated with a greater density of microglia, rather than cell activity, as in rodents.

Far-reaching impacts

According to the researchers, the findings could have far-reaching impacts for clinical research, and significant implications for the pharmaceutical industry, where it has become a widely used research tool to validate new drug candidates.

Dr David Owen, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Clinical Pharmacology from Imperial’s Department of Brain Sciences, said: “PET provides researchers an invaluable window into the brain, and TSPO has offered a useful research tool for measuring neuroinflammation.

“But we have shown that TSPO is not a marker of activated microglia, as previously thought. This doesn’t mean the technique isn’t valuable as a research tool, but in many situations it’s not as helpful as we’d previously thought, and in drug discovery it may not be fit for purpose.”

The researchers say that the TSPO PET signal should best be interpreted as showing the density of inflammatory cells in the brain, and not a reliable measure of microglial activity. They add that future work should explore new biomarkers which show promise in indicating microglial activation.

The work was supported by funding from the MRC, the UK Dementia Research Institute, MS Society, Imperial NIHR BRC, and others.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) Ryan O’Hare © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.