DeviceDiagnosticInnovation Fluorescence gives doctors a real-time connection with the health of the gut

The Imperial team asked clinical trial participants to drink a small dose of a fluorescent dye and measured the resulting fluorescence signals through the skin, which increase as the fluorescent dye leaks out of the gut into the bloodstream. By analysing the data, the team demonstrated the ability to non-invasively measure important aspects of intestinal function.

Now, Imperial has partnered with MediBeacon, a US medical technology company that has extensive experience in optimising transdermal diagnostic methods for a range of medical conditions, including measurement of intestinal permeability.

“The area of intestinal permeability as a mainstream diagnostic in clinical practice is a new concept,” says Steven Hanley, MediBeacon’s Chief Executive. “We are pleased to add Imperial to our team of collaborators in this important area of clinical development.”

A one-dye method

Existing techniques to measure gut permeability tend to be cumbersome and unreliable. Typically, they involve giving patients a dose of two sugar molecules, one a small molecule and one a large molecule, and measuring the ratio of the two in the urine. This ratio changes along with permeability.

Dr Alex Thompson’s group from the Hamlyn Centre at Imperial utilised an alternative method, based on techniques that allow fluorescent dyes in the bloodstream to be detected and measured through the skin.“Our technique is potentially much simpler, more accessible, and less costly than dual sugar tests,” says Dr Thompson. “You just attach a sensor to the patient’s skin, the patient drinks a fluorescent dye, and the data effectively collects itself over the next three hours.”

An expert partner

Through his research, Dr Thompson became aware of MediBeacon, a medical technology company specialising in the advancement of fluorescent tracer agents and transdermal (‘through the skin’) detection. MediBeacon owns several issued patents and patent applications covering methods of measuring gut permeability through transdermal detection of a fluorescent dye. Imperial’s technology covers potential improvements to these methods.

After filing a patent application covering the Imperial technology, Dr Thompson and commercialisation specialists at Imperial Enterprise decided to reach out to MediBeacon. These discussions led to MediBeacon licensing the Imperial patent application, which aligned well with the company’s focus on the assessment of gut permeability using fluorescent agents. Meanwhile, Dr Thompson is working with the company on a consulting basis to accelerate its development of a point-of-care transdermal intestinal permeability product.

MediBeacon has an extensive portfolio of proprietary fluorescent agents and highly engineered transdermal sensors, which the company has refined and optimised over the past 15 years. It has been working on intestinal permeability, mainly through a collaborative research programme with Washington University in St Louis.

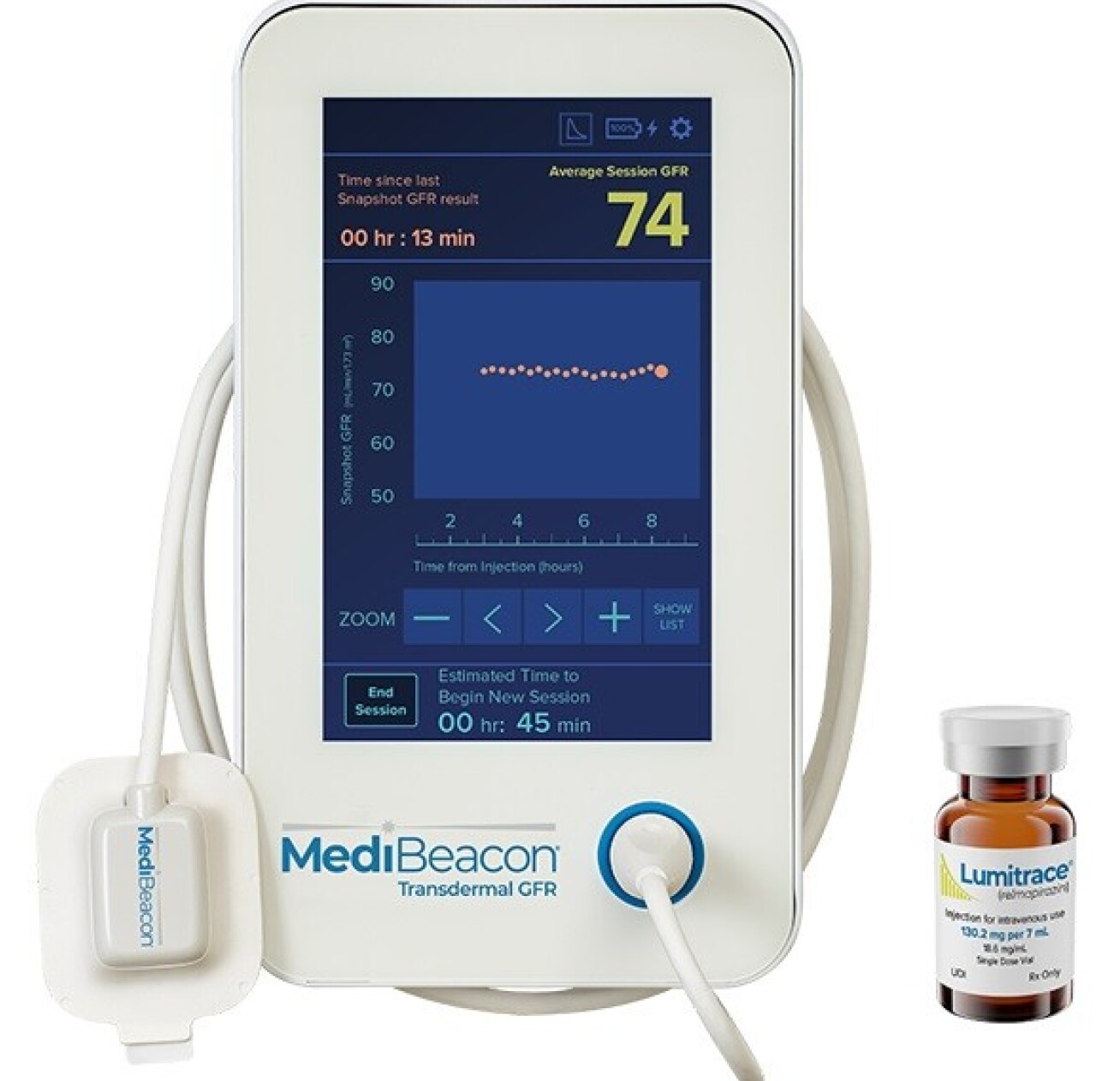

This work builds on the MediBeacon Transdermal GFR Measurement System (TGFR), which is designed to measure glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or kidney function in real-time at the point of care. The company has recently completed the TGFR Phase 3 clinical study and filed the Clinical Study Report with the US FDA.

The same fluorescent agent, Lumitrace (relmapirazin), and TGFR sensors which are central to the kidney programme are now being adapted for use in the measurement of intestinal permeability.“We are looking forward to evaluating improvements that Alex and his team will make on the optical detection of transdermal fluorescence, and we anticipate that these improvements could be incorporated into our commercial instrumentation,” says Dr Richard Dorshow, MediBeacon’s Chief Scientific Officer. “In addition, learnings from clinical studies that Alex and his team will conduct should prove to be useful in the optimisation of future clinical studies for specific gastrointestinal indications.”

Continuing academic work

Meanwhile, academic work developing and testing the method will continue at Imperial and is a key objective of the Digestive Disease Theme. Clinical trials have already shown that the data collected with the technique agrees well with existing methods, and can measure gut permeability changes in both healthy volunteers and patients.

“We have an ongoing clinical trial using this method in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and our preliminary results look very promising. The early data suggests that we can differentiate healthy people and those with inactive IBD from active IBD,” Dr Thompson says. “We are also using this technique, along with several other technologies, to monitor the function of the gut in malnutrition, in collaboration with a group in Zambia.”

Both the Imperial researchers and MediBeacon are interested in producing wireless and wearable devices. Beyond bedside tests for gut permeability in the clinic, this opens the way for monitoring at home. “For patients with inflammatory bowel disease who have gone on to a new treatment, we might ask them to take this test once a week, to monitor how they are responding to the therapy,” Dr Thompson says.

Through their collaborative work, Imperial and MediBeacon hope to drive improvements in the diagnosis and monitoring of IBD as well as other intestinal diseases.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London – original article can be found here Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.