Interview Interview with a researcher, working to improve healthcare- Daniel Leff

Daniel Leff is a Reader in Breast Surgery in the Department of Surgery and Cancer at Imperial College London and an Honorary Consultant in Oncoplastic Breast Surgery at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. He is also a member of the NIHR Imperial BRC Surgery and Cancer Theme.

Daniel’s research focuses on improving people’s experience and outcomes in breast cancer surgery.

He co-led the primary radiotherapy and deep inferior epigastric perforator flap reconstruction for patients with breast cancer (PRADA) trial which found that changing the order of treatments given to breast cancer patients could reduce side effects and improve outcomes.

“Whilst I see myself as a breast cancer surgeon first and foremost, research enables me to have a much greater impact, well beyond the patients I treat directly. It enables us to shape future practice and improve the quality of care that cancer patients receive.

“The traditional clinical pathway of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy left women waiting many months and even years for breast reconstruction after their operation.

“I wanted to do better for them. By offering radiotherapy before surgery instead of afterwards, we can carry out a mastectomy (an operation to remove the breast) with immediate reconstruction.

I see myself as a breast cancer surgeon first and foremost, research enables me to have a much greater impact, well beyond the patients I treat directly.

“The PRADA study proved this is both feasible and safe. I am now applying for funding for a follow-up study comparing pre-operative radiotherapy with post-mastectomy radiotherapy for surgical, oncological, and breast reconstruction outcomes, including quality of life.

“My main research passion is to be able to operate with greater precision. Historically, surgery for breast cancer has been rather imprecise – especially in operations that aim to preserve the breast.

“As a surgeon, you only want to remove the tumour and leave as much healthy breast tissue as possible. You remove what you can see and aim to take a ‘safe’ margin around the edges, so that no cancer cells are left behind to re-grow. But if you cut too close to the edges of the tumour, or fail to cut it all out, then the patient will need another operation a few weeks later to remove more tissue.

“Sometimes that can happen more than once and may eventually lead to a mastectomy, which can be distressing and traumatic.

“That makes me want to push boundaries. Obviously, that requires a team effort, and I love being part of the academic community at Imperial: we have a truly multi-disciplinary approach.

Historically, surgery for breast cancer has been rather imprecise – especially in operations that aim to preserve the breast.

“Some of the innovations we’re working on bring together engineers, technicians, doctors, designers and healthcare economists. Individually, none of us has the knowledge or skills to overcome the challenges of improving breast surgery outcomes. But together, we are designing, creating and trialling new surgical methods.

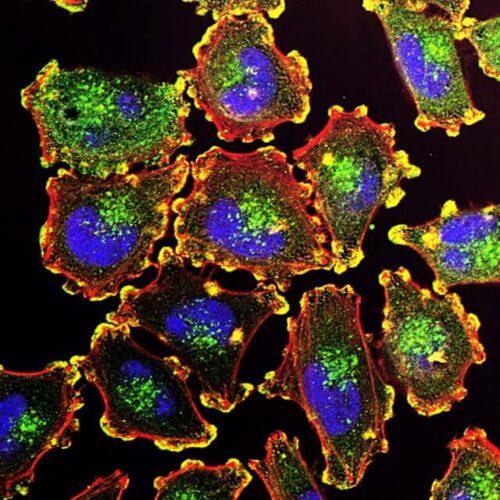

“For example, we have the GLOW project to tag cancer cells with fluorescent, glow-in-the-dark probes that allow us to see the tumour while we’re operating, or under a camera immediately after the tumour is removed. This means we know straightaway whether we need to remove more tissue and only have to operate once.

“We’ve also just completed our first REI-EXCISE trial, testing the intelligent knife (‘iKnife’).

“ The iKnife is based on electrosurgery, a technology invented in the 1920s that uses an electrical current to rapidly heat tissue, cutting through it while minimising blood loss. In doing so, it vaporises the tissue, creating smoke that is normally sucked away by extraction systems.

Going forward, I would love to see governments working together to make it easier to create, fund and carry out joint research projects across multiple countries.

“Our engineering colleagues realised we could connect the iKnife to a machine that would analyse the smoke plume coming off cells as they’re being cut. So, again, we know almost immediately – within 1.8 seconds – whether they’re cancerous.

“It has been really exciting to be involved in taking this project from development in the lab to its first-ever clinical trials in the operating theatre.

“I’ve learnt many things from my research. The two most important are that collaboration is vital – across disciplines, hospitals and countries – and that patient-reported satisfaction is often as important an outcome as the clinical markers we set for ourselves.

“Going forward, I would love to see governments working together to make it easier to create, fund and carry out joint research projects across multiple countries.

“As a single surgeon, I might be able to sign up tens of patients to a study. As a centre, we might manage hundreds. Across the UK that could even be thousands, but internationally we would be able to recruit the numbers needed to give us definitive evidence that our innovations are working and translating into patient benefits.

“One of the best things about research is that it extends your impact as a clinician beyond what you can physically achieve with your own hands.

“For devices that are at a pilot stage and not yet commercialised, I think that’s going to be very challenging, but it makes complete sense!

“I’m also keen to continue our innovation with early detection of breast cancer. We’ve just finished a project called Mammobot. This is where we are trying to engineer a robot to diagnose cancer by inserting a very fine endoscope (a long thin tube with a camera inside it) in the nipple-areola, for minimally invasive intervention. I’m now working on identifying funding to take this project to its next stage.

“One of the best things about research is that it extends your impact as a clinician beyond what you can physically achieve with your own hands.

“Of course, there are challenges: you need lots of energy and resilience to bounce back when ideas don’t work, or funding bids don’t come good. You have to move out of your silo and talk to lots of people – funders, patients, designers, engineers, clinicians in other specialities, but together the opportunity for us to make a difference is enormous.”

This interview with Daniel Leff is adopted from Humans of Health Research- Interviews with researchers and patients working together to improve healthcare.